Pacific Mammal Research is Giving a Voice to Two Undercelebrated Puget Sound Marine Mammals

You don’t have to tell us twice that Puget Sound has an abundance of incredible wildlife (we started this entire project because we’re endlessly fascinated by all of it!). While our giant cetaceans tend to steal the show (and the funding), Puget Sound is also home to thousands of species of invertebrates, hundreds of fish and bird species, and dozens of species of marine mammals. Luckily Pacific Mammal Research is giving a voice to a couple of the commonly seen, but rarely celebrated marine mammals — the harbor porpoise and the harbor seal, and their recently published paper ‘Adapting photo-identification methods to study poorly marked cetaceans: a case study for common dolphins and harbor porpoises’ can be found here.

Cindy and Kat graciously invited Sara into the field with them to see what a field day looks like and also answered all of her burning harbor porpoise + harbor seal questions.

This interview has been lightly edited for length.

Can you both describe your path to studying marine mammals?

Cindy: I grew up in New Mexico and Virginia, but most of my school career was in New Mexico. Living in the desert wasn’t exactly conducive to studying marine mammals, but for as long as I can remember I loved dolphins and other marine mammals and always wanted to work with them. I have a journal saved from 6th grade where the journal prompt was “I want to be…” and my answer was … “a dolphin and whale researcher, I want to work with them”. I can’t say where that all began, I just can’t remember thinking anything different.

After graduating from high school in the desert I went in search of the ocean. I was afraid of earthquakes (so California was out), so I went to the East Coast and Florida for college (yes there are hurricanes, but you know those are coming and can leave if you want!). I did my undergraduate studies there and participated in some week-long programs with the Dolphin Research Center in the Florida keys. With the help and guidance of a professor in school I realized I could do dolphin research for my master’s program. He was integral to me getting to work with The Wild Dolphin Project and starting my career as a marine mammalogist as a graduate student with them. That turned into becoming a research assistant, getting my PhD (which wasn’t my plan in the beginning!) and now having my own research project, while still being a research associate with WDP.

Kat: I grew up in the Shetland Islands (Scotland) and was fortunate enough to live right on the water. I got to watch marine mammals right outside my window while I was growing up, which sparked my curiosity and love of marine biology. I knew in my heart marine mammal science was all I really wanted to do, so I decided to attend the University of St Andrews for my undergraduate and master’s degree (they have an amazing Sea Mammal Research Unit there — some of the top researchers in the field and are the only university that offers a master’s degree in Marine Mammal Research!).

“Looking into the eye of another highly intelligent, social animal was so amazing, and further solidified my desire to learn more about them and help protect them.”

Do you remember the first time you saw a marine mammal in the wild?

Cindy: I can’t actually remember the first time I saw a wild marine mammal, but I do remember the first time I got to be in the water with spotted dolphins when I started working with WDP. I got in the water and a mother and calf in the group came over and I made eye contact with the mom (within a foot or two). WDP’s motto is “in their world, on their terms” so we just observe. Looking into the eye of another highly intelligent, social animal was so amazing, and further solidified my desire to learn more about them and help protect them.

Kat: Hmm, not the first time, but I do have an early memory of seeing orcas in the Inlet just outside of our house when I was really young. We also had a sperm whale come into that same estuary when I was in grade school, and even got a halfday at school so we could all go down to see it — that was incredible!

What brought both of you to Puget Sound and, ultimately, to starting PacMam?

Cindy: It all started because my husband and I didn’t want to live in Florida anymore. lol. I was also teaching at a charter high school after funding with WDP ran out. I wanted to get back into research, and applied for a position with another group out here. My husband got a great job out here and we moved out, My work with the other group ended up not working out after a few months, but I met Kat through them (she was our intern), and I realized I wanted to start my own project where we could conduct the research we were interested in. Luckily Kat was totally up for that crazy adventure :)

Kat: I did an internship in Friday Harbor on the San Juan Islands in 2009 and absolutely fell in love with the area. I had moved quite a bit as a kid, but can honestly say I had never experienced the feeling of “home” until I arrived here! I was still at University, but vowed to find a way to get back to the San Juan Islands one day. That day came in 2014 when I applied for and accepted an internship with another group in Anacortes. That’s where I met Cindy, and when she asked me if I wanted to move here permanently to help her start and run a non-profit there was only one answer! :)

You’re involved in so many fascinating things with PacMam. Can you describe the work that you’re doing and your goals with Pacific Mammal Research?

Cindy: Our main goal is to learn as much as we can about both harbor porpoises and harbor seals so this information can be used in policies that create meaningful biological conservation measures. The old saying “you can only protect what you understand” is at the heart of what we do. There is so much to learn about these species, and particularly harbor porpoises which have been traditionally overlooked, so we do a lot!

Our main project is to follow individuals over time and to use photo identification of both species to identify and track individuals. We document behavior and relate this to environmental information about when and why they are at a particular location.

We are also interested in looking at their acoustic environment and have started deploying a passive acoustic device to try to better understand their vocalizations and the soundscape they live in. We will also be able to connect vocalizations we record with behavior that we observe in our field sessions.

We are looking into doing eDNA, where we take sea water where a porpoise just surfaced and can extract porpoise DNA from it! From this we could learn so much more about their genetics and how that correlates to their group and population structure and dynamics.

“I believe very strongly that by knowing the individuals we can better understand and protect them, so being able to do this for both species in one place was a wonderful combination.”

Why did you choose to focus your research on harbor porpoises and harbor seals?

Cindy: I came out to work with that other group at first who were studying harbor porpoises. That got me more interested in this species, especially because there is so little known about them. We have so much to learn and that got me excited, especially because almost no one had spent time trying to do photo-ID on harbor porpoises, so I wanted to see if we could do it. I have always been a supporter of the underdog species, so these guys go along with that.

The harbor seals are in the area, and we know less about them as individuals as well. I believe very strongly that by knowing the individuals we can better understand and protect them, so being able to do this for both species in one place was a wonderful combination.

Kat: As Cindy said, in some ways the species we study were dictated by our origins, but since then we have learned so much more about how understudied harbor porpoises are, despite being one of the most commonly seen cetaceans in their range! Like Cindy said, there is an incredible paucity of data around how these animals live in the wild and for me it was very exciting to be at the forefront of this emerging area of study.

A harbor porpoise photographed underwater in Kerteminde, Denmark (Photo: Solvin Zankl)

What’s one thing you wish everyone knew about harbor porpoises?

Cindy: That they are cooler than people think! And that they exist at all. lol. So many people don’t know we have porpoises here even though they are the most abundant cetacean species in the Salish Sea. These small, unassuming animals are very interesting.

Kat: That they’re an indicator species. I think everyone assumes they’re “doing fine” or that there “must be loads of them, we see them all the time”, but in fact harbor porpoises are just as susceptible to ecosystem changes as any other species. Changes in their populations can be an indication of changes in the larger ecosystem, and as such are a really important species to study over the long term.

What about harbor seals?

Cindy: That they aren’t eating all the salmon. They eat salmon, but they also eat 60+ other species, too. Also, harbor seals can sleep for 30 minutes underwater! That is just a cool fact.

Kat: I would second Cindy’s answer! Out here there is a prejudice against harbor seals as “taking all the fish”, but that’s simply not true.

The cutest harbor seal swimming past the PacMam field site on Fidalgo Island (Photo: Sara Montour Lewis)

This photograph is available as a print in our shop and 20% of the proceeds from sales of this print will be donated to PacMam to help support their incredible work with marine mammals in the Salish Sea.

Cindy, from the PacMam podcast I know that you’re on a bit of a mission to make sure people understand that there’s a difference between a porpoise and a dolphin. Do you mind setting the record straight for us on what the distinctions are?

Cindy: Yes!! There are 4 main differences:

Dorsal fin — Dolphins have a more curved, or falcate, dorsal fin while porpoises have a more triangular dorsal fin (but, as we are finding out, there is a bit of variation in that!)

Face — Most dolphin species have a beak or a rostrum, porpoises have a blunt face with no beak/rostrum

Teeth — Dolphins have cone shape teeth and porpoises have spade shaped teeth

Behavior — Dolphins are generally more gregarious/social in larger groups and are not usually found alone while porpoises are usually in smaller groups and can be often found alone. However, the topic of sociality is debated — many say porpoises aren’t social at all, but I don’t think that is true, I think it just looks different than dolphin species. That is something I am very interested in learning about.

There are an estimated 700,000 harbor porpoises worldwide and ~15,000 in the Salish Sea alone, but there are still so many gaps in our knowledge about them. Can you touch on some of the reasons why there’s still so much that’s unknown about this species?

Cindy: Because they are difficult litter buggers. lol. They are small and they don’t have many obvious or easily seen markings. They are also fast, evasive and often surface erratically, which makes getting photos of them very difficult. They don’t like boats like other dolphin species do, so again their behavior makes them difficult to study. Along with that, there are many other species (at least here in the Salish Sea) that are easier to study, and thus the harbor porpoises have been forgotten. Orcas and larger whales, and even seals and sea lions, get more of the attention.

Kat: Agree with all Cindy said. I would also add that they have so little coverage in both the scientific and public media spheres that many people don’t even know they exist! If they do, again, there’s this assumption that their populations “must be doing fine”, so no one tries to study them.

Are there challenges in researching a species with a high population that differs from studying a species with a limited, or even endangered, population?

Cindy: Yes! The more animals you have, especially over a wider area, makes it more difficult to be able to reach them all and really get their whole range and population in the study, so any large population is going to be difficult. The other part of that is that since they are doing well finding funding and even interest in studying them is harder. Since there are other species that are in more difficult situations, or need more immediate action, they get more attention and funding. But it’s important to study the animals before they get to that point so we can stop them from getting to that point! An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, but we often don’t think that way unfortunately.

Kat: Yup, everything Cindy said! Again, I would just really highlight that one of the biggest obstacles to studying a species with a high population is the lack of interest or funding. In addition to the limitations and problems with studying harbor porpoises we already mentioned, the fact that they’re not in immediate danger of going extinct means there’s very little incentive for funders to support our project.

Dozens of harbor seals hauled out on logs near Jetty Island in Everett, Washington (Photo: Sara Montour Lewis)

If you had unlimited time/resources/budget is there one burning question that you’d love to be able to answer about harbor porpoises?

Cindy: Oh, there are so many!! But I want to know what their social structure is — do they have long-term friendships and relationships? Do they live in smaller communities within the Salish Sea or as one large community? My master’s and PhD were on social structure in dolphins, so I am really interested to see what porpoises do.

Kat: I would love to know how, and to what extent, they communicate with one another! My background is in acoustics, and for so long we believed that harbor porpoises didn’t even vocalize — it turns out we just couldn’t hear them because they produce ultrasonic clicks! I would love to know what they’re saying to one another and how that information is encoded in their clicks — or do they have other calls and cues that we don’t even know about yet?

When I saw that you were using photo identification to track individual animals I was amazed and so intrigued. There are so many harbor porpoises and harbor seals in our waters that I couldn’t quite wrap my mind about how you were able to track individuals. Can you talk a little bit about the process of photo identification and the role it plays in your work?

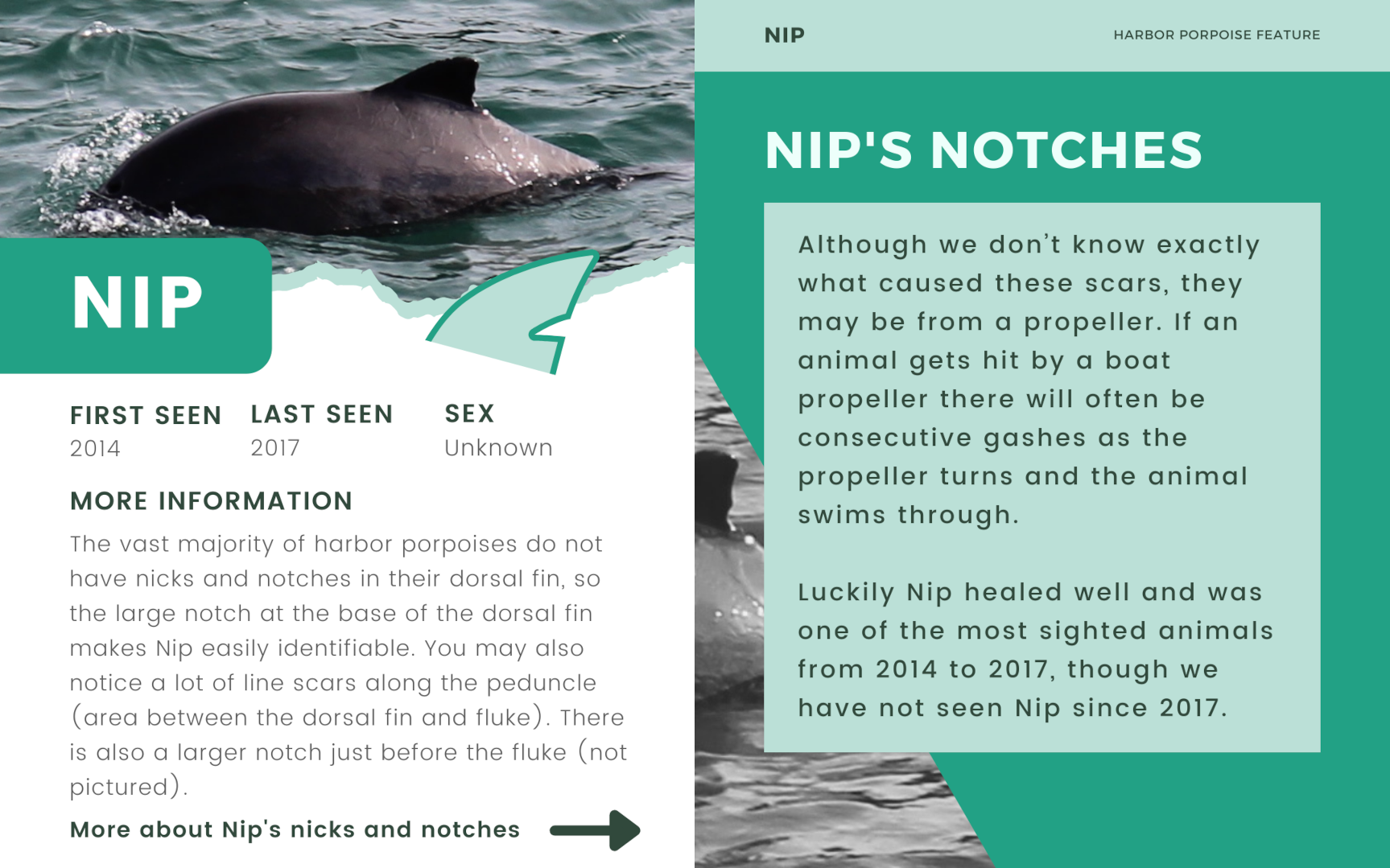

Cindy: Photo identification is the process of tracking individuals over time using stable natural markings. By comparing photographs taken on different days, year, and even from different locations, we can use those natural markings to tell individuals apart. As long as a mark is stable over time it can be used (marks can change over time, but if you can track that change by getting regular photos you can still use it). These marks include nicks or notches in the dorsal fin, spotting patterns, scars, pigmentation on various body parts, edges of flukes, edges of ears, even coloration of painted crayfish! The important thing about this is that it’s a non-invasive way of tracking individuals (as opposed to tagging).

In social animals it’s imperative to understand who the individuals are to understand (and to somewhat predict) their behavior and their social/population structure. It can tell us how large an individual’s home range is through distribution and movement patterns, more about their life history (like when and how often do they have calves), how old can they get, their habitat use patterns, human interactions and conflict, site fidelity, etc. Information we need to know in order to protect them.

Orcas are a great example - we know so much about those animals, and what they need for survival, because we know the individuals. That knowledge is critical!

PacMam has put together these great ID cards on some of the individual harbor porpoises that they’ve seen come through their field site at Burrows Pass

What identifying features do harbor porpoises and harbor seals have that enable you to track individual animals?

Cindy: Harbor porpoises have unique pigmentation patterns on the side where dark turns to light, along with scars on the body and sometimes a distinctive dorsal fin shape. (they usually don’t have nicks/notches in the dorsal fin which is what most other small cetacean photo-ID uses). We actually use an 8 category matrix of marks to help confirm the IDs because they are more difficult to ID than other species.

Harbor seals are more simple - their spotting patterns are unique, so we can find a cluster of spots that stands out to us and use that to ID individuals.

Is there something specific about the ecology of Burrow’s Pass that makes it an ideal location for this research?

Cindy: That is a question we are trying to answer — it seems to be a biologically important area to these species. They mate, bring their calves, ride waves/wakes, and forage here. There is something about the productivity there that makes it a good place to be. We are working to define what that is.

Kat: As Cindy said, this is something we’re trying to answer, but the high tidal flow in this area is especially important. High tidal flow areas are often associated with greater levels of productivity and/or activity by marine species, so this is likely a factor in why Burrows Pass is such a great spot for these creatures.

View of Burrows Pass from Anacortes, with the PacMam field site to the right (Photo: Sara Montour Lewis)

I’ve seen a couple of great images that you’ve taken of harbor porpoises wake surfing, which is a behavior that scientists didn’t traditionally associate with them. Have there been examples of other behavior that you’ve observed through field research that contradict what we’ve previously assumed about this species?

Cindy: I think that harbor porpoises do more things than we think, it’s just that people haven’t spent enough time watching them to see it! They do leap out of the air (all the way sometimes) and we have learned that that is almost always connected with mating attempts (at least in our site). We also have documented them eating large fish like salmon and American Shad (it looks to be mostly females doing this), even though they typically eat things less than 30 centimeters.

They aren’t as adverse to boats as most people think. With engines off they will come by pretty close sometimes and in the Pass they don’t seem to be that bothered by boats — they just move away or dive until it is through, then go back to what they are doing.

We have seen adults and calves logging sometimes, which is where they just sit on the surface like a log for 3-10/15 seconds, contrary to the fast moving they do most of the time.

I also have one picture of a spyhop!

Kat: Everything Cindy already said! :) Also just the fact that they aren’t solitary animals — as Cindy already mentioned there’s an assumption about harbor porpoises that they aren’t social, yet we frequently see them in groups of 2-3 or larger, which does indicate that they form associations even if they are short-term ones.

A harbor porpoise stealthily swimming through Burrows Pass (Photo: Sara Montour Lewis)

I’m guessing that you two have incredibly full plates already trying to collect and interpret all of this data, but then on top of it you’re actively running Pacific Mammal Research, as well. What lessons have you learned from starting a nonprofit that you didn’t expect?

Cindy: You have to do a little bit of everything. I was prepared for that while working with WDP because, as RA, I did everything from take the trash out to lead field trips. In this line of work it is all hands on deck, often literally. But that takes on another meaning when you are running a business (nonprofits are still businesses in the end, just ones that aren’t to get profits). That is one of the biggest lessons — that in many ways you have to run and think of it as a business and adjust for the nonprofit side of things. But to keep it going, get funds, etc. you have to think like a business person to keep that side of the project going, which is hard for us research scientists :)

Another thing: find an awesome partner that shares your passion. I started PacMam with Kat, and I couldn’t imagine having to have done it solo.

Kat: Ooo good question! I would agree with Cindy. For me the biggest lesson is around the funding side of things. I write most of our grants for funding and so for me one of the biggest takeaways that I have learned is that communication is KEY. If you can’t communicate why what you’re doing matters, you don’t get funding: it’s that simple. We as scientists tend to assume everyone understands the value of learning more about a species, and the value of preemptively protecting their populations, but that’s not the case!

When you aren’t scanning the horizon for marine mammals do you have any favorite ways to pass the time on (or in) Puget Sound?

Cindy: I love hiking, though whenever I am near water I can’t help but scan and look. lol. I like to run and enjoy our beautiful scenery. My son, daughter and I also like to camp. And of course spend time on the beach.. You’ll notice most of my interests aren’t far from the ocean :) I wish I could get out on boats more often, but hopefully that will be changing this year with getting our PacMam boat up and running more regularly.

Kat: I love to hike as well, and spend time exploring the different islands in the San Juan Islands archipelago. My boyfriend is a sailor so I have been fortunate enough to start exploring the area by boat in the last few years, which has been incredible!

What are the most helpful ways for people to support PacMam?

Cindy: As a small nonprofit donations make the biggest impact. It is hard for us to compete with larger organizations for grants and, unfortunately, long-term monitoring is not a well-funded topic. People want to see direct impacts to save species or ecosystems, but what isn’t well understood is that to do those things you have to know about the species, their ecosystem, and how they interact. You can’t make good conservation decisions without good knowledge of the organisms you are affecting, so long-term monitoring is critical to have this data that you can then use effectively. Finding funding for that work is hard and we rely on private foundations and public donations to continue our work.

Sharing our information with others is extremely helpful, too. The more people know about the work we do, and are educated by the knowledge we provide, the better informed citizens will be to make the choices that will have positive impacts on the animals. This impact helps show our impact both locally and globally, which in turn can help with receiving grants and funding.

Finally, they can volunteer with us! We have a pool of volunteers that either come out with us or do their own sightings for us. We need help in the field to collect all the data and citizen scientists collect more information for us than we could on our own. This increases the data we have to be able to ask the questions we want to know about. We can’t be everywhere, so the more eyes we have out there looking the more data we can collect and questions we can answer.